Kristal Haynes, Hunter College Office of Assessment, June 30, 2014

Q: What is a rubric?

A: From Carnegie Mellon University’s Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence and Educational Innovation –

“A rubric is a scoring tool that explicitly represents the performance expectations for an assignment or piece of work. A rubric divides the assigned work into component parts and provides clear descriptions of the characteristics of the work associated with each component, at varying levels of mastery. Rubrics can be used for a wide array of assignments: papers, projects, oral presentations, artistic performances, group projects, etc. Rubrics can be used as scoring or grading guides, to provide formative feedback to support and guide ongoing learning efforts, or both.”

Q: Does having access to a rubric prior to completing an assignment improve student performance?

A: Providing rubrics prior to grading and/or involving students in rubric construction is related to an increase in student performance.

Reddy and Andrade (2010) conducted a literature review of 20 empirical studies analyzing rubric use in higher education. They found that:

Student Perceptions of Rubrics

- Andrade & Du (2005) and Bolton (2006) found that students perceived rubrics as helpful for reducing uncertainty in their ability to meet the criteria of the assignment, allowed them to reduce the amount of effort needed to complete the assignment and helped them estimate their grades prior to submission.

o Powell (2011) found that having access to rubrics before grading improved student attitudes about feedback/grades.

- Researchers suggest that for student-centered learning, rubrics should be used not just as grading tools but also as instructional guides, which means that students should have access to prior to completing an assignment.

The Impact of Immediate Access to Rubrics on Student Performance

- In a quasi-experiment on rubric impact on performance, Petkov & Petkova (2006) found that students with access to a rubric prior to grading had, on average, a significantly higher grade percentage on an assignment compared to students who did not have access prior to grading.

- Reitmeier, Svendsen & Vrchota (2004) compared student performance in two different semesters where students did and did not have access to self and peer assessment rubrics prior to being graded. They found that the average assignment grade increased as well as the average overall course grade. The instructors attributed this process to having access to rubrics throughout the semester.

- To contrast, Andrade (2001) found that simply administering rubrics to middle school students did not significantly affect grades but rather engaging in constructing a rubric with students led to an increased in performance.

In summary, having access to a rubric prior to completing an assignment helps students focus their efforts, clearly understand feedback and the grading process and may lead to a slight increase in performance.

*Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448. doi:10.1080/02602930902862859

Q: Does having access to a rubric prior to completing a writing assignmentimprove student writing?

A: It is unclear.

Andrade (2001) conducted a study looking at the use of “instructional rubrics” on improving student writing. Two hundred and forty two 8th grade students from diverse racial/ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds attending middle schools across California were sampled. One group of students (the treatment group) was given instructional rubrics to guide three different writing assignments during the school year. A comparable control group was not given instructional rubrics to guide their performance on three different writing assignments. The assignments were scored by the principle investigator and a team of research assistants.

In analyzing the effects of access to a rubric, the researchers found mixed results. The treatment group scored significantly higher on just one of the three assigned essays compared to the control group (the second assigned essay). The author attributed the lack of overall impact on the quality of the rubric and the timing of the assignments. In addition, all students completed a questionnaire assessing their understanding of assignment criteria. Students in the treatment group showed better understanding of what was expected in their writing as compared to the control group.

In summary, instructional rubrics can increase student knowledge of expectations but translating that into improving the writing process is still somewhat unclear.

*Andrade, H.G. (2001). The effects of instructional rubrics on learning to write. Current Issues inEducation, 4(4). http://cie.ed.asu.edu/volume4/number4

Q: Are there useful alternatives to using rubrics for assessing student writing?

A: Though a large amount of literature focuses on the use of rubrics for grading, there are alternative assessment tools that can successfully replace rubrics.

Quite a few resources examining writing assessment discuss the importance of using alternative assessment techniques for grading student competencies in a holistic, formative context that is learner-centered. Listed below are a few examples of alternative writing assessment methods.

Example 1: Portfolio-Based Writing Assessment

Portfolio-based writing assessment is the collection of writing samples and assignments which demonstrate student progress and competency over the course of a term. There are several variations on how portfolios can be constructed and assessed. A portfolio can serve as a holistic way to analyze whether or not learning outcomes are being achieved, can keep documented record of the progression of learning and is a fairly popular “process-oriented” assessment practice in the U.S. A 2003 study found that students exposed to a process-oriented writing assessment produced writing that was more elaborate and better organized than students whose work was examined in a “product-based” manner (Cho, 2003).

Romova & Andrew (2011) examined the use of “multi-draft” writing portfolios in English-as-an-Additional-Language classrooms across northern Europe teaching adult learners. Multi-draft portfolios allow the student to edit their collection of writings and, in the case of this study, allowed students to reflect upon the overall process (this is described as a “process-oriented pedagogy”). The authors conducted a grounded theory qualitative analysis of student reflective writings and interviews and found four main emergent themes. The majority of students 1.expressed frustration with understanding the technique and need for referencing in writing, 2. became more aware of discursive forms, 3.grew to value the editing process and 4.grew to appreciate teacher feedback.

In summary, a process-oriented portfolio assessment is considered useful as a formative teaching and grading tool when it comes to examining student writing. Qualitative analysis of student assignments and reflective writing can also be conducted to examine whether or not learning outcomes are being accomplished.

*Cho, Y. (2003). Assessing writing: Are we bound by only one method? Assessing Writing, 8(3), 165-191.

*Romova, Z. & Andrew, M. (2011). Teaching and assessing academic writing via the portfolio: Benefits for learners of English as an additional language. Assessing Writing, 16(2), 111-122.

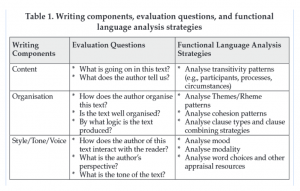

Example 2: Functional Language Analysis

Fang & Wang (2011) suggest that “functional language analysis” is a useful alternative to the use of traditional rubrics for grading student writing. The authors argue that rubrics are not successful at improving the student’s learning and development and are often unclear even when the goal is to clarify expectations. Functional language analysis “…offers a set of analytical tools that enables teachers to focus systematically on the language choices students have made in their writing and evaluate whether these choices are appropriate for the particular task at hand and effective for presenting information, creating discursive flow, and infusing perspectives” (pp.149 – 150). This kind of analysis recognizes the contextual nature of writing and communication and focuses assessment on appropriate language use for the particular context.

See below for an example of functional language analysis grading criteria:

In summary, Functional Language Analysis can allow instructors to grade writing based on the context of the assignment in conjunction with adherence to evaluating traditional writing standards.

*Fang, Z. & Wang, Z. (2011). Beyond rubrics: Using functional language analysis to evaluate student writing. Australian Journal Of Language & Literacy, 34(2), 147-165.

Example 3: Grounded Theory Approach (Qualitative Analysis of Writing)

Authors Migliaccio & Melzer (2011) suggest that grounded theory, traditionally used in qualitative research, can be a useful tool for assessing how faculty assess student writing and the accomplishment of learning outcomes. Grounded theory analysis is a method that allows for exploration of a phenomenon in an inductive manner by searching for common themes in the context of the writing. Faculty can assess the achievement of course objectives and program objectives by looking at all or a sample of student papers and editors’ comments. After this process is complete, coders can review faculty comments for common themes that emerge in order to guide the course revision process (or assignment revision process). This particular method provides a framework for examining common trends among students.

In summary, a Grounded Theory Approach can be useful in reviewing group level accomplishment of student learning outcomes and can be a measurement used to assess if course content and assignments are helping students meet these goals.

*Migliaccio, T. & Melzer, D. (2011). Using grounded theory in writing assessment. The WAC Journal, 22, 79-89.

Example 4: Assessment Through Collaborative Critique

Authors and instructors Robbins, Poper & Herrod (1997) approach the process of student writing from a feminist and social constructivist perspective, framing the experience for their students as noncompetitive, collaborative and nonhierarchical. The “action research” project (sometimes alternately labeled “participatory action research”) that emerged was a collaborative effort involving the students and instructors from inception to completion. This allowed the authors to acknowledge the social aspect of learning to write and allowed students to see, experience and reflect on this process while creating work to be evaluated.

Students across three different primary, secondary and post-secondary classrooms were asked to write letters to each other to practice the genre of letter writing. The letters were not graded and the process of learning involved the composition of the letter, later revisions, small and large group discussion of the work along with reflective writings on the project. All three instructors participated writing and sharing letters as well. Students and parents were made aware of the learning objectives and were continuously asked for their insight and reflection throughout the study. Results showed that students were able to revise their work in anticipation of their audience, all of who would not be in their classroom or in their age group. They were also able to compare and contrast the difference in writing levels, techniques and letter content among the age groups. Most of the students, especially the middle school participants, were eager to write back to their counterparts and showed an increase in enthusiasm. Due to the popularity and success of this project, instructors decided to create a similar collaborative project for creative writing.

In summary, the authors suggest that low-stakes, ungraded collaborative writing can be a useful supplement to graded work and/or can be used to construct a portfolio for assessment. They also found that having the freedom to use student writing for discussion in large groups allowed for clear instruction on good examples and errors that needed correction.

*Robbins, S., Poper, S. & Herrod, J. (1997). Assessment through collaborative critique. In S.Tchudi (Ed.), Alternatives to Grading Student Writing (pp.137–161). National Council of Teachers of English.

Example 5: Achievement-Based Assessment

Achievement based assessment, according to Tchudi & Adkison (1997), grants higher end-of-term grades to students who produce a body of work that is higher in volume, quality, creativity and depth. Grades can be granted on a points based system, though the authors/instructors expressed a future desire to avoid numerical grades altogether. Students who pass each assignment based upon the assessment criteria and submit high quality work are given rewards to compensate their efforts and achievements. This approach is similar to a “checklist” approach combined with a token approach, often seen in alternative classrooms and reading and/or scouting programs focused on motivating student achievement within a particular period of time for reward or recognition.

Adkison structured a freshmen-level English composition class by using achievement based assessment to grade student writing. The author established criteria for earning an “A” or a “B” in the class (to focus students on higher v. lower achievement; some students earned C’s due to lack of attendance and lack of basic work completion). The tasks to accomplish during the term included maintaining regular attendance, creating and maintaining an informal writing journal for reading response and reflection, participating in specified field-trips, writing a series of essays and creating a final portfolio of work. Full completion of these requirements in addition to the pursuit of a project of the student’s liking (graded as “credit”/ “no credit”) would lead to the highest grade.

In summary, removing the intense focus on both grades and producing work that would “please” the professor can lead to increased risk-taking and a focus on the quality of the work being submitted.

*Tchudi, S. & Adkison, S. (1997). Grading on merit and achievement: Where quality meets quantity. In S. Tchudi (Ed.) Alternatives to Grading Student Writing (pp.192-208). National Council of Teachers of English.

References

Andrade, H.G. (2001). The effects of instructional rubrics on learning to write. Current Issues inEducation, 4(4).

Cho, Y. (2003). Assessing writing: Are we bound by only one method? Assessing Writing, 8(3), 165-191.

Fang, Z. & Wang, Z. (2011). Beyond rubrics: Using functional language analysis to evaluate student writing. Australian Journal Of Language & Literacy, 34(2), 147-165.

Migliaccio, T. & Melzer, D. (2011). Using grounded theory in writing assessment. The WAC Journal, 22, 79-89.

Reddy, Y., & Andrade, H. (2010). A review of rubric use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation In Higher Education, 35(4), 435-448.

Robbins, S., Poper, S. & Herrod, J. (1997). Assessment through collaborative critique. In S.Tchudi (Ed.), Alternatives to Grading Student Writing (pp.137-161). National Council of Teachers of English.

Romova, Z. & Andrew, M. (2011). Teaching and assessing academic writing via the portfolio: Benefits for learners of English as an additional language. Assessing Writing, 16(2), 111-122.

Tchudi, S. & Adkison, S. (1997). Grading on merit and achievement: Where quality meets quantity. In S. Tchudi (Ed.) Alternatives to Grading Student Writing (pp.192-208). National Council of Teachers of English.